Imagine waking up at 10 AM on a Saturday, only to realize you have a brunch reservation in 30 minutes. Your reasoning immediately kicks in. You need to dress, brush your teeth, shower, dry your hair, check the bus schedule, etc. These actions have dependencies and constraints—you can’t shower and check the bus at the same time, but you could brush your teeth while showering. At every moment, you’re making decisions: what do I do now, and what can wait?

One can model the current state as branching into a tree of possibilities. We define reasoning as identifying a trajectory from the current state to the goal. We know this is possible in token-space because reasoning models were all the hype of 2025, starting with OpenAI’s o1 and later DeepSeek R1. But what about implicit reasoning? Can we train a model that reasons over its depth?

To answer this, I devised a new problem. Given a tree and a goal node, start at the root and identify the edge that takes you towards the goal node. Since the graph is a tree, the number of possible paths to its leaves grows exponentially in the branching factor.

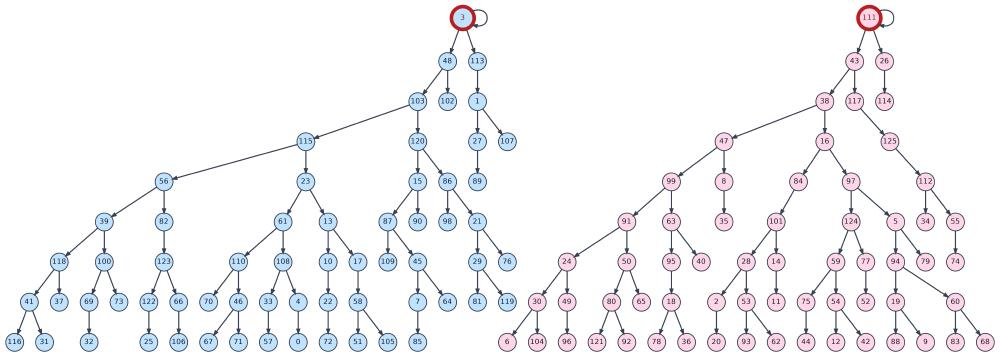

An alternative formulation: start with $N$ trees and, given a goal node, ask for the root of its tree. In the example below, if the goal is node $116$, the target is node $3$. The root nodes (highlighted) represent immediate next states. In our metaphor, this is like asking whether the state where you make it to brunch on time lies on the tree where you first rush into the shower (good choice) or the one where you first check Instagram (you won’t make it).

Experiments

For the dataset, I generated $12.5$ million pairs of binary trees, each with up to $9$ levels and $63$ nodes (see above). For the model, I took a modified GPT-2 architecture1 and removed the MLP layers, using a head dimension of 256 and scaling from there.

I ran three main experiments.

1. What algorithm does the model learn?

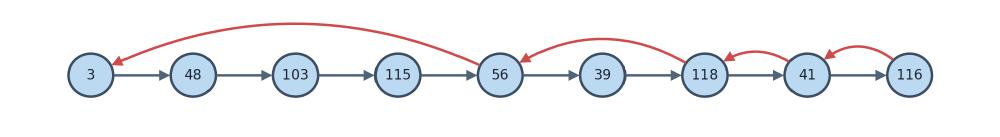

A simple algorithm is to backtrack from the goal node to the root. If done for every child node in the edge list, the number of iterations is $\mathcal{O}(\log H)$ for a node at depth $H$. Since our trees have 9 levels, the path from the deepest level to the root requires only 4 steps. The process works as follows: the first step uses positional encoding to identify each child node’s parent, then the remaining three steps recursively copy the parent’s parent until reaching the root.

We include a self-loop at each root node to simplify the recursion and avoid a dynamic number of iterations. If the goal is a root node, we iterate in-place and return it.

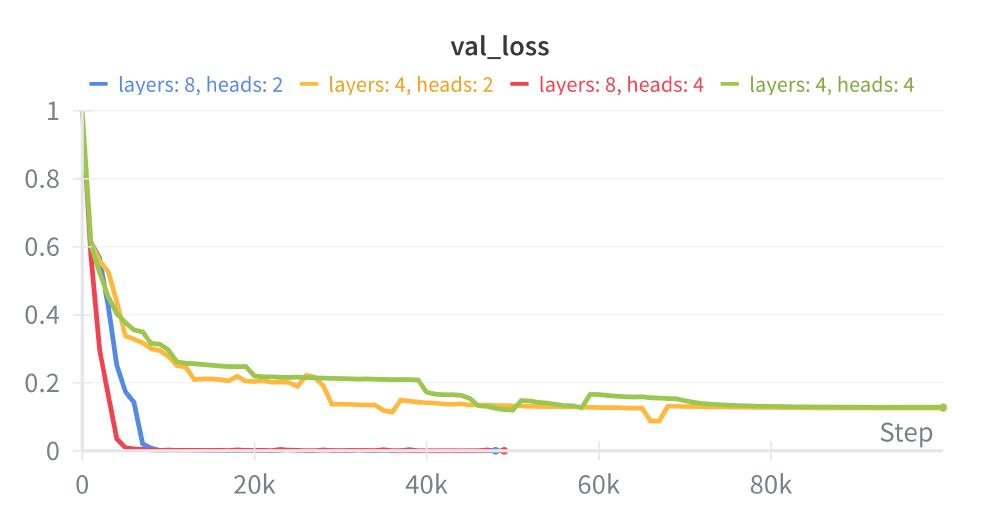

Based on this algorithm, we expect a Transformer to require at least $4$ attention layers and $2$ attention heads (one for backtracking, another to determine token type: parent, child, or goal). In preliminary runs with only $3$ layers, the model fails to learn beyond random guessing past level $5$, as expected. With $4$ layers, it succeeds at predicting the correct root even for nodes at level $9$, indicating that the model learns the log-time algorithm.

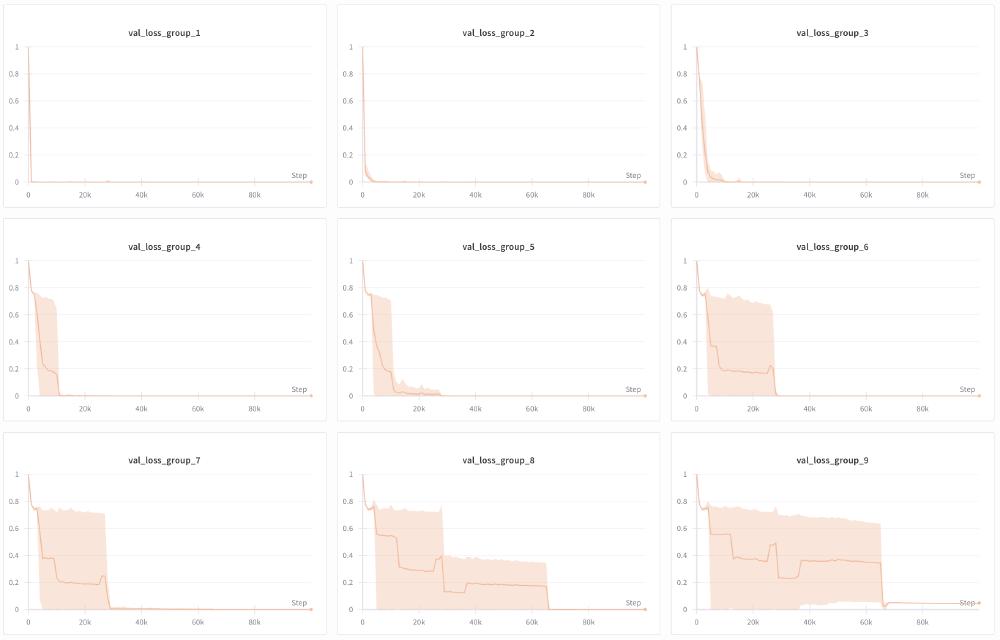

The plots below show average validation loss for goal nodes at levels $1$ through $9$ during training. Unsurprisingly, loss decreases rapidly for root nodes first, then takes longer for each subsequent level because a $k$-hop backtrack subsumes all $i$-hop backtracks for $i<k$. In one (omitted) run, the model failed to reduce loss past level $6$, but the rest succeed.

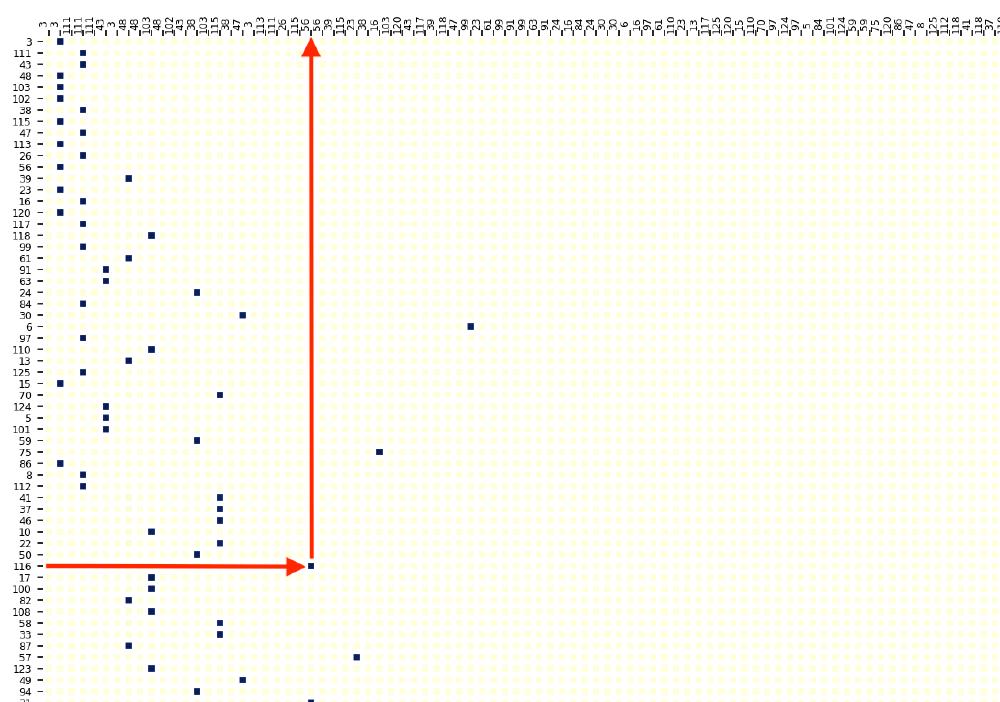

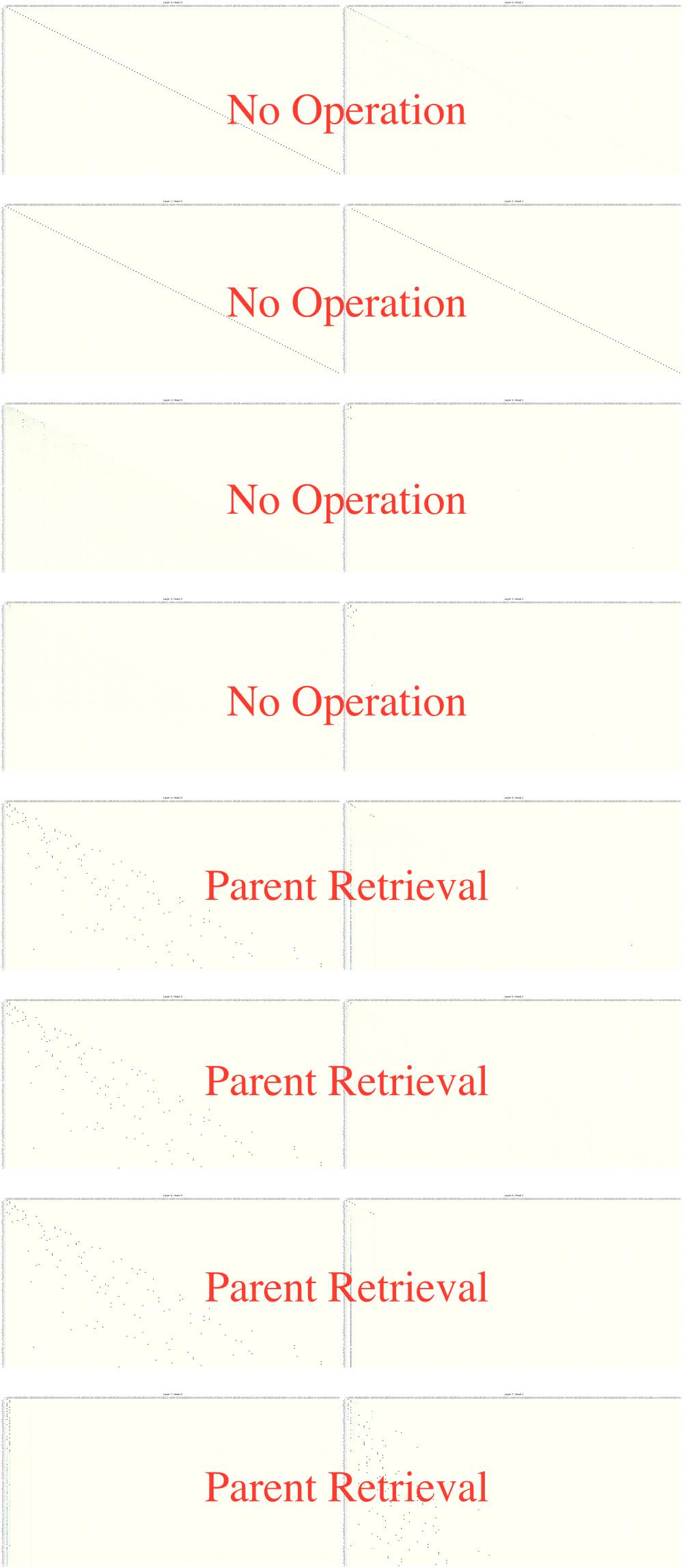

Analyzing the model’s attention weights for the pair of trees shown earlier further verifies the learned algorithm. The plots are massive, so I’ll show just one attention head from the last layer as an example. Query tokens (child nodes from the edge list) are on the y-axis; key tokens (parent and child nodes in alternating order) are on the x-axis. As expected, token $116$ queries the parent of token $56$ which returns node $3$ (the root).

In summary, we’ve shown that a $4$-layer Transformer model is capable of $8$-hop backtracking using a log-time algorithm in a single forward pass. This result is corroborated by a recent paper2 that studied the ability for Transformers to perform search using their depth.

2. What if we vary model size?

With this toy problem, we can easily vary model size. I ran experiments comparing an $8$-layer model (vs. $4$) and a model with $4$ attention heads (vs. $2$). My hypothesis was that increasing depth or width would help the Transformer learn the correct algorithm more reliably, since both expand the space of representable circuits. Averaging over $5$ runs, the results suggest depth matters more than attention head count for convergence.

The attention weights of the $8$-layer models were mostly difficult to interpret, in stark contrast to the $4$-layer model. Amusingly, one model learned to attend to the current token for the first four layers, spending half its depth on no-ops, then behaves like a $4$-layer model.

In summary, adding layers was beneficial for faster convergence, while increasing the number of attention heads did not have a significant effect.

3. What degree of supervision is necessary?

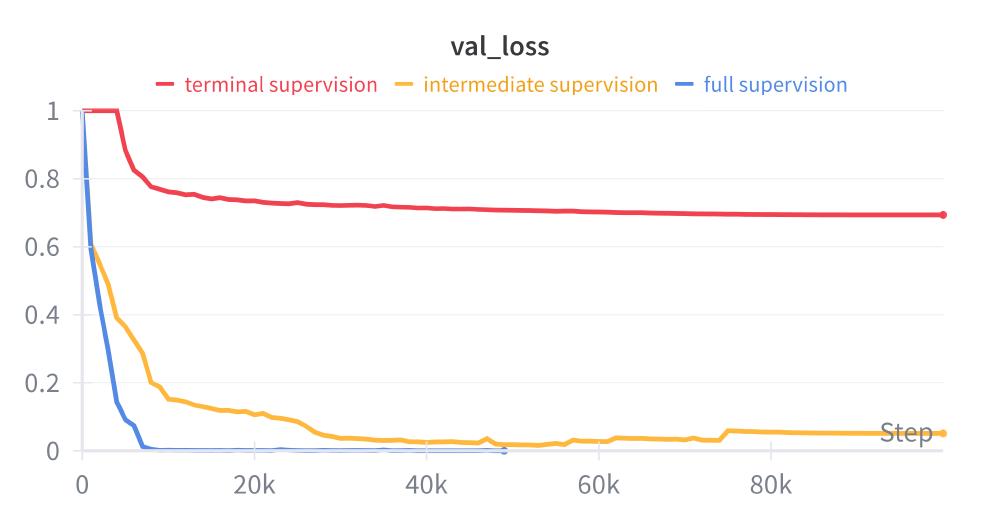

So far we trained with goal nodes from every level in the tree. In real-world datasets, only partial supervision may be available and the model must fill in the gaps. To test this, I compare full supervision (every level) with two partial schemes: intermediate (every other level) and terminal (only the last three levels).

Over $10$ runs with the $8$-layer model, intermediate supervision gets close to perfect performance but converges more slowly. Terminal supervision learns that the output is always one of the two root tokens, but never progresses past random chance; its average final validation loss is $0.69$ and $e^{-0.69} = 0.5$.

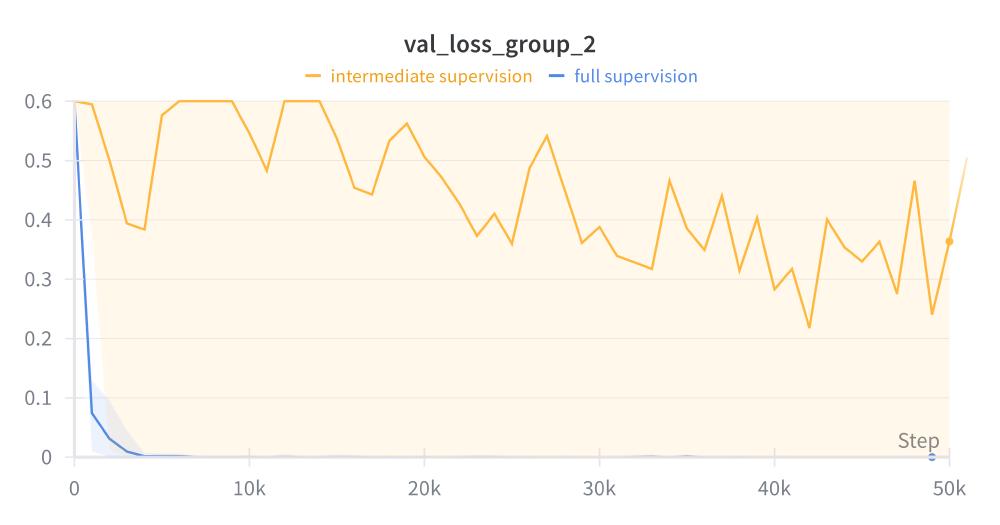

Interestingly, even when validation loss converges to zero, a model trained with intermediate supervision does not necessarily solve the problem for unsupervised levels. As shown above, even for level-$2$ nodes, some models fail to return the correct root while others succeed. This also occurs for $4$-layer models and illustrates how difficult it can be to teach a model the correct algorithm without precise constraints.

In summary, full supervision is not required for a model to reduce the loss at deeper levels, but it is necessary for the model to consistently learn the intended algorithm.

Closing Remarks

I hope these experiments have provided some intuition about how Transformer models can reason over their depth, rather than relying on long token trajectories.

Although I drew an analogy to human reasoning, there is a key difference: during inference the Transformer backtracks and identifies the root for every node, then returns the root for your goal node. This is why the model only needs $\mathcal{O}(\log H)$ layers, whereas human reasoning seems more sequential and lazy.

A good example of this idea comes from Zeyuan Allen-Zhu’s Physics of LMs paper series. When they train a GPT-2 model to solve Grade School Math problems, they find:

Before any question is asked, it already (mentally!) computes with good accuracy which parameters depend on which, even though some are not needed for solving the math problem.3

Concretely, this means that in a question that starts with “Sally has 10 apples and Bob has 5 apples”, the model has already pre-computed the response to questions like “how many more apples does Sally have?” or “what is the total number of apples between them?”.

This is both a strength and a weakness. On one hand, the model does not have to generate extra tokens to reason about basic questions since their answers are pre-computed. On the other hand, this cache is built regardless of the question, which can be inefficient. The trade-off is data dependent.

For future experiments, I would like to expand from trees to directed graphs with varied structures. This is a more realistic setting, allowing for loops and multiple paths from root to goal.

I am thankful for Google’s TPU Research Cloud, through which I was able to run all my experiments.